The C&O Canal National Historical Park ranks as one of the area’s prime recreational resources, although its storied history includes nearly being paved over to develop a highway to downtown Washington, D.C. Today, the National Park Service oversees this scenic stretch of land, and has been successful at preserving the land, flora, fauna, and many historic sites along 185 miles of the Potomac River’s left bank. The restored canal towpath is now a popular multi-use trail, with detours where hikers can savor nature and even find solitude. The landscape you see today has been shaped in different ways by both natural and manmade forces.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal had its origins in a grand ambition voiced by Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and other early American leaders. Their goal was to make the Potomac River navigable and link it to the Ohio River valley. The Potowmack Company, chartered in 1785 with George Washington as its first president, announced it would clear a channel and build skirting canals around the rapids. Immigrants were welcomed to do the heavy lifting of many physical obstacles that hampered progress. It took nearly 20 years just to complete the canals. The channel was never cleared completely, and boat travel was severely limited by fluctuating water levels. The Potowmack Company eventually collapsed.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company, launched in 1828, inherited its predecessor’s charter and property. Its plan was to stay out of the river and build an on-land canal dotted with locks and paralleled by a towpath for the mules and horses that would provide the motive power for the boats. The canal was not finished until 1850—eight years after the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad had reached Cumberland—so the canal was already largely obsolete commercially. The Civil War and recurrent floods further damaged the canal and its toll-based business. After a devastating 1889 flood, the waterway was bought by the B&O. The C&O Canal remained in sporadic and local use until 1924, when another flood led the B&O to abandon it. In 1938 the railroad gave it to the federal government to settle a $2 million debt.

The National Park Service managed to restore the canal’s lower 22 miles before World War II intervened, but did little else for a long time thereafter. In 1954 a public campaign launched by Supreme Court justice and outdoorsman William O. Douglas saved the canal route from being paved over as a parkway. In solidarity, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy invited his press corps to accompany him on a 50-mile hike from Great Falls, Maryland to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Both of these influential leaders brought attention to the canal’s natural beauty. Congress made the property a national monument in 1961 and a national historical park in 1971.

Located just outside the beltway, on MacArthur Boulevard, you’ll find ample parking, but prepare to pay an entrance fee per vehicle of $10. Of all the hikes on the C&O Canal, this section is probably the most popular because of its access to the thundering cascade of whitewater called Great Falls. To view Great Falls Overlook from the Maryland side, you will walk along man-made boardwalks and concrete bridges through the wetlands of Olmstead Island. There are crossing points that are a bit scary to some, but the effort is worth it for this panoramic view of the Potomac’s mightiest waterfall.

After parking, find your way to the Great Falls Tavern Visitor Center to check out the museum and retrieve a map. Rangers are usually available to answer questions about the hiking trails. The building was originally a lockhouse in the late 1820’s where canal operators lowered and raised the locks for canal boats to proceed upstream carrying coal from Maryland’s western counties south to Georgetown. The Visitor Center has restrooms, weekend bike rentals, and it’s where visitors may pay $8-$5 fee for a mule drawn canal boat ride. The Charles F. Mercer Canal Boat operates on weekends from the end of March until October 30 at 11:30 am, 1:30 pm and 3 pm (but it’s worth checking before you go). On some weekends you might see living history encampments with re-enactors dressed in Civil War uniforms.

The trailhead crosses over a bridge just past the Visitors Center and proceeds south on the towpath. After Lock 18, you will see the entrance to Olmstead Island. Follow this path into the fairylike woods, where boulders are covered with lichen, hardwood trees are decorated with moss, and lush grasses and thistles grow. As you continue to pass over the protected wetlands on the boardwalk, you’ll come to two precarious concrete bridges where you’ll cross over chutes of swiftly moving currents of water tumbling over steep rocks. After that excitement, prepare to walk single file down narrow passages until you reach the Great Falls Observation Deck. Across the Potomac River, you may see your fellow hikers on the Virginia side. In good weather, kayakers enjoy playing around at the base of Great Falls. To return to the trail, retrace your steps.

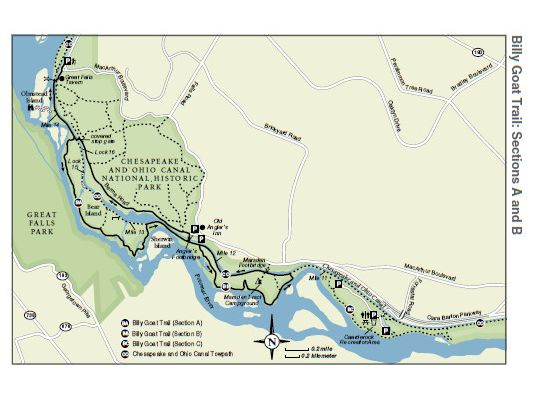

After you return to the towpath, turn right. Just after Lock 17, you will pass the entrance to Billy Goat Trailhead Section A. The arduous and very popular trail requires scrambling over angled rocks and boulders for 1.7-miles. It’s quite challenging, especially when there are lots of people, but it offers breathtaking views and a great workout.

For this towpath hike, you will continue walking on the dirt towpath, all the while watching out for bikes by staying to the right. The towpath is a favorite for parents taking the kids for a stroll and dog owners giving their dogs a nice stretch. If you come here on weekday mornings, you might find groups of high school kids collecting water samples for their biology class.

At Lock 15, the trail becomes a boardwalk. Around this point, the canal opens up and widens to an expansive view. This section is called Widewater, and there are two shady benches if you want to rest for a minute and enjoy the view. Look to the right, on the Potomac River side, for ponds where turtles sun themselves on fallen tree trunks. A little further down from Mile Marker 13, you’ll see another entrance to the Billy Goat Trailhead A.

It’s time to turnaround when you get to a wooden bridge, which leads to the rustic Old Angler’s Inn restaurant, parking lot and bathrooms. This is where most of the kayakers come to put in. You can either turnaround and retrace your steps, or in fine weather, you can go up and have a snack or meal at the restaurant’s outdoor patio. If you prefer not to retrace your steps, take the Berma Road Trail on the eastern side of the C&O Canal. Berma Road is 1.5-mile return trip to Great Falls Tavern Visitor Center.

Directions: From the Capital Beltway I-495 take exit 41 toward Carderock/Great Falls for .3 miles. Merge onto Clara Barton Parkway. Go 1.5 miles and then make a slight left onto MacArthur Boulevard. Go 3.4 miles to the entrance of the C&O Canal National Historic Park, 11710 MacArthur Boulevard Northwest, Potomac, Maryland.

Leave a comment